German election, China's AI Rise, and the MAGAfication of Big Tech

What the German election means for Europe, how China's DeepSeek is challenging EU AI policy, how US tech companies (and the EU) are already bending to appease Trump

Welcome back!

We hope you had a restful, European-style (long, mostly offline and disconnected) break.

This week, we’re diving into three main stories:

The German election: Where do parties stand on AI, industrial policy, and competition? And what does this mean for Europe?

China’s new ‘open’ AI model: DeepSeek 3 is here. And it’s challenging some core assumptions about EU AI policy.

US tech and Trump: How US tech companies—and the EU—are already bending to appease Trump ahead of the inauguration on January 20.

Plus, we’ll catch you up on Nvidia bracing for a possible cooling down, OpenAI making losses and claiming AGI is within reach (again), the growing legal headaches facing AI, and other news on the environment, regulation, and defense.

#1 - The German election

Germany’s political parties are now officially in full election mode, having rushed to complete their political programs ahead of the federal election on 23 February.

What’s at stake?

The election’s outcome will have a ripple effect on European politics, including on artificial intelligence (AI) and especially on industrial policy. Simply put, agreement between Germany and France is a precondition for advancing even the most modest proposal on industrial policy and public investments. (Don’t worry, we’ll dive into France in an upcoming issue.)

With conservative Friedrich Merz likely to become the next chancellor, German voters face three pivotal questions:

Who will be the junior coalition partner? And where do they differ with the front-runner CDU/CSU?

Who will lead the opposition?

Which parties will secure enough votes to enter parliament?

German politics - a primer for the perplexed

Since reunification, Germany’s political landscape has grown increasingly complicated. Five parties are poised to cross the 5% threshold required to enter the Bundestag:

The conservative Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU)—the political home of Ursula von der Leyen—is currently leading the polls (32 %).

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is second (20%), but a broad (though gradually eroding) consensus against cooperation means they’re not going be part of the next government.

The Social Democrats (SPD) (16%) or the Greens (13%) are likely coalition partners - with a SPD-CDU/CDU coalition currently looking most likely.

The newly founded Bündnis Sarah Wagenknecht (BSW (6%), a new party combining left-leaning economic policies with right-leaning stances on migration and a pro-Russia orientation, is expected to gain parliamentary representation.

Meanwhile, two established parties—the Left (3%) (Die Linke) and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) (4%) — risk losing their seats in parliament.

Germany’s AI dreams

Despite deep-seated ideological divides, most parties agree that AI is an opportunity that Germany cannot miss. While differences exist, broader questions about AI’s direction remain largely unaddressed. Here is where the parties stand:

The center-right CDU sees “sovereign AI” (and cloud applications) as a prerequisite for competitiveness and “reindustrializing the country.” To shape the development and use of AI systems, the CDU bets on “high-performance digital infrastructures” (i.e. robust data centers, and compute for research and SMEs). The CDU also sees the European Chips Act and the European Semiconductor Alliance (ESRA) as key towards more sovereignty and less dependency. In the public sector, the CDU hopes AI will lead to faster and more efficient delivery of services (while allowing citizens the right to individual reviews).

The far-right AfD’s position on AI can be explained through the party’s opposition to the EU (principally opposing EU industrial policy or tech regulation), its nationalism (aspiring to world-leading AI “made in Germany” powered by cheap energy), its xenophobia (using AI to close skills gaps and curb non-EU immigration), and its neoliberalism (subsidizing chips is “wasted taxpayer money”).

The Social Democrats endorse sweeping industrial policy (on AI and digitization more broadly, on strengthening sector-specific AI ecosystems, and on the development of LLMs for applications in medicine, materials research, and education), while strengthening workers’ participation and co-decision rights on AI adoption, and increasing the efficiency of public services through automation and AI. The party also strives for fair compensation for artists and funding social innovation and project on AI.

The Greens also endorse industrial policy, albeit with a focus on supporting AI applications and digital business models in the private sector, while reducing “data protection bureaucracy,” and investing in production capacities for chips and batteries. The party also emphasizes protecting civil liberties and human rights while safeguarding artists’ copyrights. The Greens hope automation, including through AI, will make public services more efficient and support an EU-wide reform of procurement rules.

The BSW calls for “freely available” AI models and open-source software in science, education, culture, and the public sector. They criticize Europe’s dependence on U.S. tech giants, describing the continent as a “digital colony.”

The liberal FDP wants German leadership in AI with a special emphasis on liberating training data through more “innovation-friendly” enforcement of the AI Act, and building European data centers, while favouring sweeping use of AI and automation to make public services more efficient.

The Left’s program says little about AI but warns against replacing teachers with educational technology. The party also support breaking up digital monopolies and encouraging platform cooperatives.

Coalition fault lines

The previous German government (SPD, Greens, FDP) suffered from internal conflicts. A two-party coalition might seem simpler, but prepare for fault lines and difficult negotiations, whoever wins the election.

Likely points of contention are:

Fiscal responsibility: A CDU-led government seems unlikely to support sweeping Draghi-style public investments if that means increasing Germany’s federal budget deficit. The CDU opposes reforming Germany’s balanced-budget constitutional amendment, while the SPD and Greens see a reform as over-due.

Competition enforcement and reform: Don’t expect German support for antitrust enforcement to fade under a CDU-led German government, but don’t expect radical reform either. The SPD and Greens advocate robust antitrust policies (albeit with slightly different emphasis), while the CDU prefers a lighter touch. The Conservative election manifesto offers only a vague commitment to “fair competition” and “modern antitrust and competition law” in Europe, while condemning competition authorities’ “generalized suspicion” toward businesses.

AI Act enforcement: A CDU-led German government coalition will likely be divided on how to implement and enforce the AI Act. Nobody in Germany loves the Act (as those who remember Germany trying to block its adoption will recall). Positions vary from the Greens’ calling the Act an “important foundation that needs to be implemented unbureaucratically," to warnings about “over-compliance,” and “overregulation” hampering innovation (CDU).

AI industrial policy: a fragmented picture

Germany’s next government will likely back the EU’s agenda on AI capacity-building but without a clear strategy. CDU, SPD, and Green proposals on AI industrial policy all tend to be high-level and based on the assumption that boosting blanket AI adoption and development will increase productivity, lead to economic growth, and deliver efficient public services. We challenged this premise in our EU AI industrial policy report.

Under which conditions, and towards what end, AI should be supported is inherently contentious (and largely absent from the respective political platforms). Proposals range from strengthening lower levels of the AI stack (chips and cloud), to building LLMs. We found no convincing strategy for exactly how sovereignty, competitiveness, or more independence – lofty goals that nearly every party aspires to – can be achieved in either of the parties’ programmes.

Key blind spots

Notably absent from party platforms:

AI’s Environmental Impact: Surprisingly missing, even from the Greens

Labour and the Workplace: Only addressed by the Social Democrats (with some reference to creatives by the Greens)

AI’s direction: No program contains a real vision for how to shape AI’s trajectory

Outlook for Europe

Count on Germany’s next government as a voice that favors strengthening Europe’s AI capacity, including through industrial policy (as long as it doesn’t cost too much!).

However, don’t expect Germany to provide leadership on strategy or direction.

Expect inner-German conflicts on fiscal responsibility (again!), competition enforcement, regulatory stringency, and priorities on industrial policy.

#2 - Echoes from China

In the past few months, there have been important developments in the Chinese AI market. Deeper corporate partnerships have been announced between prominent AI labs and Chinese tech giants, with 01.AI, Moonshot AI, and Zhipu AI all raising significant funding rounds from the likes of Tencent and Alibaba.

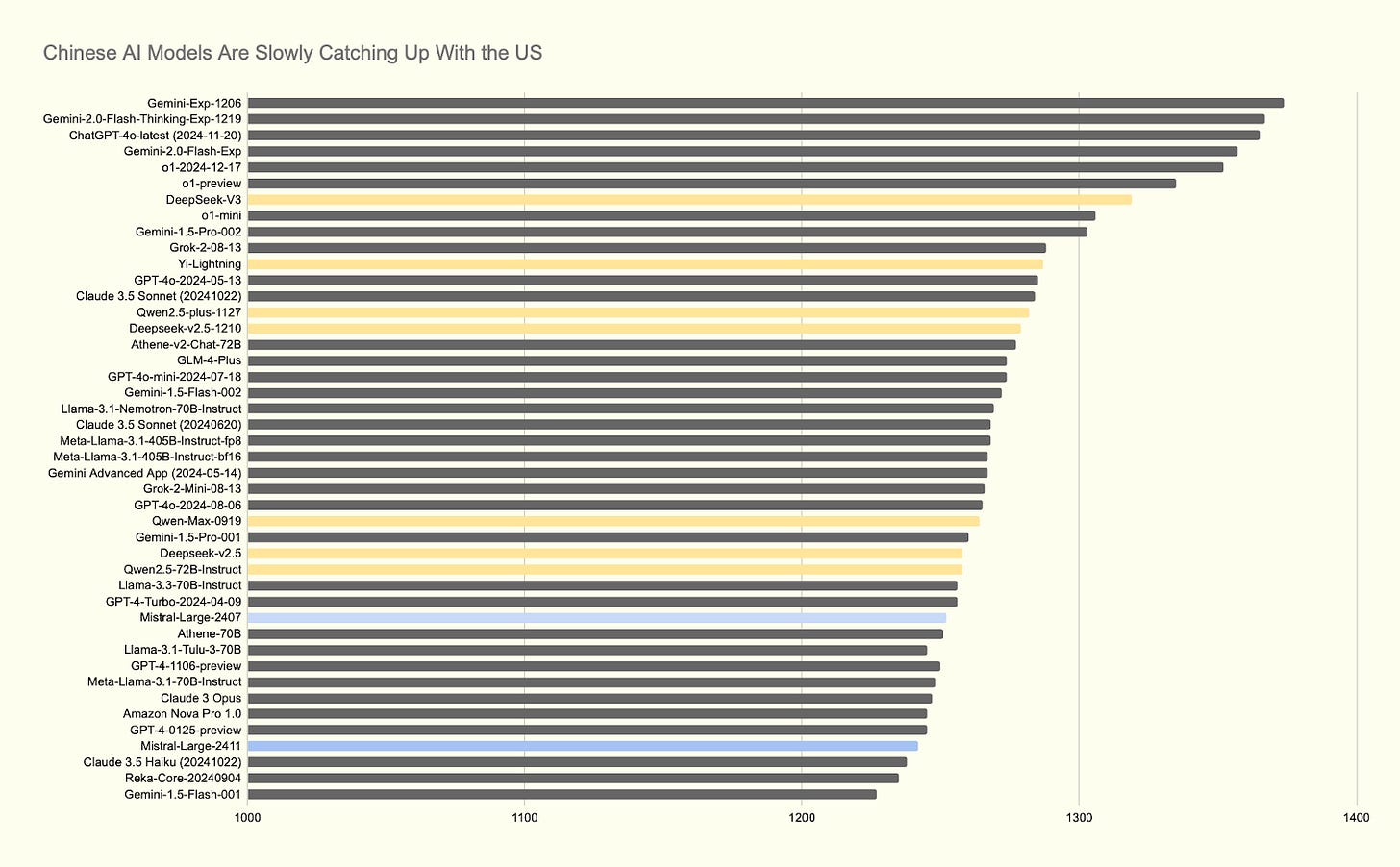

Meanwhile, the capabilities of the Chinese models have been slowly catching up with the American AI champions, despite limited access to GPUs.

One Chinese upstart that has recently caught the attention of Western observers is DeepSeek, a spinoff of a Chinese quantitative trading firm, which released a new “open” large language model, V3 just before the new year.

What is notable about DeepSeek

The model beats many proprietary rivals on popular benchmarks, such as the widely followed LM Arena (read AI Now’s Chief Scientist Heidy Khlaaf’s comments here) and it can be downloaded and modified for most applications, including commercial ones.

Most noteworthy is DeepSeek’s claim that it spent less than 6 million USD for the final training run of the model - a small sum compared to the cost of developing models like OpenAI’s GPT-4, estimated at 100 million. While this does not include the computation used for experimentation, it is still comparatively small.

The model also needs to comply with Chinese regulatory authorities, meaning you won’t get an answer when asking critical questions about issues that are subject to censorship within China (don’t ask about Tiananmen, Uyghurs or Taiwan, see image below).

What DeepSeek means for Europe

We’ve previously questioned conflating the computational power used to train a model with its capacity and the risks it poses. If you need another example, DeepSeek’s capabilities show the weaknesses of current regulatory paradigms based on a fixed number of floating-point operations in defining a model’s capacity. DeepSeek comfortably passes below the current EU AI Act compute thresholds for models that pose systemic risks, even though it surpasses the capabilities of larger models (e.g., GPT-4, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Mistral Large 2, Llama 3.1 405B and Grok-2).

This has downstream implications for regulatory coherence, and adds pressure for the Commission to designate models as having “systemic risk” ad hoc (in line with Art 51(1)(a)), or to adjust the compute thresholds (51(3) of the AI Act).

Building massive pretraining computing clusters in the EU and in the US may not be the only pathway to “stay competitive” in an AI arms race. Assuming that the data on computational power used for training is correct, this is another sign that more capability can be extracted from less training compute than was previously assumed. However, serving this model still requires significant computational capacity so the increasing infrastructural demands at inference (and resultant environmental concerns of large-scale AI) will persist.

DeepSeek’s in-build censorship, raises a host of questions about freedom of expression, content moderation, and platform accountability in LLMs: who decides? How transparently are decisions being made and communicated to users?

#3 - The MAGAfication of Big Tech

We’ll write about in more detail over the coming months, but this newsletter would not be complete without a short take on the opportunistic repositioning by leading US tech companies in light of changing political and cultural winds (Apple CEO Tim Cook, Open AI’s Sam Altman, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon donating $1 million USD to Trump’s inauguration, Elon Musk’s aggressive endorsement and platforming of the European far-right, and Mark Zuckerberg ’s U-turn on platform accountability).

As we’ve argued in our November newsletter, for Europe, a key issue to watch is whether the closer merging of tech and state power, and a more belligerent US, might constrain the EU from implementing industrial policy, or adopting and enforcing regulation that directly challenges the interests of companies under the MAGA umbrella.

We are starting to feel the first reverberations of the upcoming changes: for the time being, von der Leyen has decided to pause ongoing investigations against US platforms – Apple, Meta and X, Le Monde reports in a shift of tech regulation closer towards high politics. Meanwhile Members of the European Parliament are putting pressure on the Commission to investigate attempts by Elon Musk to influence the German election by hosting a livestream with Alice Weidel, leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party on his platform.

What this means for Europe

Many of the background assumptions that have structured tech politics seem to slowly melt into air. A more coarse perspective on diplomacy, increased hostility towards administrative rule–making, and an America first-attitude in approaching the tech ecosystem undermine the fickle international political foundation on which transatlantic tech regulation has rested on for the past few years. How this dynamic will evolve during the Trump administration will shape the extent these shifts constrain the policy-space available for the EU.

#3 - In other news

Nvidia parachutes

In anticipation of the possible cooling down off the investments in large scale AI infrastructures by US hyperscalers, Nvidia seems to diversify its bets to alternative computational infrastructure and other customers to soften the impending correction when the large scale AI scaling paradigm starts to wither:

Nvidia moves towards robotics with AI models for humanoid robots and releases a new automotive chip and announces a big deal with Toyota to use Nvidia self-driving car technology.

Nvidia also entered the laptop market showcasing Project Digits, a personal supercomputer that processes sophisticated AI models locally in desktop friendly size.

AI phones may be an opportunity to protect the chip industry if data centre spending declines, states Nvidia supplier.

The Dutch government holds talks with Nvidia to support the construction of an AI facility in the Netherlands.

In 2024 Nvidia invested $1bn across AI deals emerging as a major backer for start-ups eager to profit in the AI revolution.

OpenAI

OpenAI’s ChatGPT Pro plan is losing money as people use it more than anticipated, says Altman. The Information reports on the varying pricing strategies of OpenAI and other AI firms.

Altman claims that he knows that AGI is within reach (again):“We are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it. We believe that, in 2025, we may see the first AI agents “join the workforce” and materially change the output of companies. We continue to believe that iteratively putting great tools in the hands of people leads to great, broadly-distributed outcomes.” Read AI Now’s journalist in residence, Brian Merchant’s essay on “the rise of AGI and the rush to find a working revenue model.”

AI meets the lawyers

Anthropic reaches agreement on ‘AI guardrails’ in a lawsuit over music lyrics

Apple agrees to pay $95million to resolve lawsuit over company accused of Siri eavesdropping on people

Google’s call for FTC inquiry into the Microsoft OpenAI deal is likely to falter.

Dutch privacy watchdog urges speeding up pace of process of standardization under EU AI Act to create certainty.

The UK’s Competition and Market Authority flags 'significant risks’ from procurement collusion and trials AI tool to detect bid-rigging

Polish presidency

Poland’s Presidency of the Council of the EU commenced on January 1st. Competitiveness is not part of the agenda.

Environment, regulation, defense

The German news Tagesschau reports excess heat from data centers is getting captured and reutilised (e.g. for heating buildings) which can cut costs and reduce emissions. New data centers installed from 2026 are obliged to reuse a portion of its excess heat. Stockholm has already implemented a similar initiative on heat recovery from data centers boosting the city’s IT sector as well as reducing the system’s emissions.

A UN advisor states that Europe is losing battle over the AI development narrative.

The co-founder of Skype shares optimism about Europe’s success in AI stressing the potential of building applications on top of existing AI models, instead of focusing on domestic capacities.

Faculty, a British AI start-up, has raised suspicions for building tech for military drones whilst also advising the UK’s government AI Safety Institute (AISI).

Thanks for reading!

As always, you can subscribe or share this newsletter.